ARTE FIERA OBSERVATORY

Cesare Pietroiusti (born 1955 in Rome) is a visual artist, founder and coordinator of many art research, design, and conference centres. Since 1977 he has exhibited in numerous private and public spaces in Italy and abroad. With a degree in psychiatry, he has always had a special interest in paradoxical or apparently irrational situations that are normally “considered too insignificant to be analysed or represented.”

MAMbo is currently presenting "Un certo numero di cose / A certain number of things," his first retrospective in a museum, curated by Lorenzo Balbi and Sabrina Samorì.

For Arte Fiera 2019, he was one of the main artists in Oplà, Performing activities, with the project "Artworks that ideas can buy".

[Editor’s note: Cesare Pietroiusti responds to Maria Morganti’s questions that were previously published in this column]

BODY OF WORK

A body of work forms slowly over time, throughout one’s life, and then you have to find a way to reflect and rethink everything.

If you look at a retrospective with a logic parallel to the work itself, like a narration flowing alongside the forms, what dimensions can it assume?

Could it be like trying not to separate two aspects of reality, art on the one hand and existence on the other?

Many years ago, when I started to make drawings (since I introduced myself as an artist, this activity – completely new to me – seemed to be mandatory), I often had the feeling that it was very hard to decide when a drawing could be considered finished. Even though I knew that both my planning and technical abilities were very limited, there was always a moment when the drawing seemed both concluded and just begun: both at the end and in the middle.

With time, this question of “unfinished” evolved into the idea that, among all human activities, the work of art is the one that already contains the future, because its meaning is not revealed once and for all, but instead is in a constant state of expectation, waiting for references, associations, surprises, discoveries, links between different spaces and times. Sometimes I made a work for a show and had the distinct feeling that it fell completely on deaf ears, and then, years later, in a completely different context, maybe during a lesson or a conference, I found that the work, when discussed with other people, could generate meanings that were unexpected even for me. So I wonder, where (and when) did I really “show” that work? At the exhibition for which it was conceived or in a classroom ten years later? And, in a wider sense, doesn’t this mean that every (and any!) new situation is potentially the ideal one for presenting a work?

Narration is perhaps the main method for creating these temporal bridges, these leaps in quality, these acquisitions of meaning. Not by documenting an event, but by experiencing its vitality, its essence, still taking place.

SELF-NARRATIVE

What happens when an artist like you, in mid-career, has to deal with a retrospective in a museum?

Why, at a certain point, did you feel it necessary to reconstruct yourself and your work?

What happens in this reinventing and rethinking of your career by means of a chronological and autobiographical self-narrative?

With reference to your life, how do you merge/separate other things, suggestions, thoughts, and signs with/from the artistic process?

How do you share your private life with your life as an artist?

It’s a challenge, amusing and maybe a bit dangerous, because a museum, through the flattery of celebration and historicization, tends to freeze the processes of transformation, criticism, and elaboration of thought. Accepting that challenge also means, in the retrospective context, involving an autobiography as a set of stories of “events” of a life, not just to reinterpret them but to see how every gesture, even if small or childish, can be linked to other subsequent gestures, events, and wishes.

It’s an a posteriori vision, but it points out that the lines linking things are there and are still there, like open valences, ready for new bonds, new reactions, new compounds.

META-ART: ART AS ART

Can this glance that flows with the work happen along the path and become a work-subject itself? (For example, I recall Simone Fattal’s work “Autoportrait, 1971-2012,” in which she filmed herself repeatedly over the years, talking about herself with complete sincerity to create her self-portrait.)

Can we consider the show itself as a work?

I think that the leap in quality and the construction of a “meta” thought, for example the passage from the thought of a singularity as such to that of it being an element of a class, is one of the most important functions of the human mind. The show at MAMbo presents the reconstruction of a collection of six works created between the late ‘70s and the late 2000s but never exhibited because, at the last minute and for very different reasons, they all seemed wrong to me.

In this case, the leap in quality from the single wrong work to their totality generates the surprising appearance of a new meaning: the class can be “right” even if all of its elements are wrong.

In recent years I’ve also insisted on the concept of reversibility. In “A certain number of things” I think there’s a sliding between the singularity of each work and the show as a single work made up of many different things – objects that precede the start of an artistic “career” or even furnishings: frames that enhance specific paintings (or drawings, etc.) or essential elements of a comprehensive narrative. A categorial sliding that can go in both directions, a reversibility between works-forming-a-show and show-forming-a-work.

OPEN THE INTERPRETATION TO OTHERS

If your work has always been a way to demolish the self-referential system, how do you reveal yourself to others in a retrospective show that by definition is autobiographical?

Can we ask other people for a vision that differs from your self-portrait?

Between your two personal themes (the development of the work and its rereading), on this sort of double track, can we ask other people to add a third one that relativizes yours?

Or, going even further, can we ask them to actively take part in a rereading of yourself and work, in a reinterpretation of everything that you have created?

At the MAMbo show, the physical centre of the scene is occupied by a ring in which a large group of young artists play with (i.e., dislocate, reinterpret, put back, etc.) everything around them: both the autobiographical narration and the works from 40 years of an artist’s career. I do this too, at least in part, along with them, going from witness to interpreter, from a guardian - of a memory, a story, a study - to the activator of a dismantling.

It’s wonderful working in a group, because it allows the appearance of thoughts that belong to everyone and to no one, that everyone feels as their own and also of the others. Of course, these are temporary conditions, but they also leave the long-lasting awareness of a different vision of the concept of author and of a different experience of the author’s supposed identity.

Dear Maria,

Thank you so much for your interest! May I add a post-script? It seems that when John Cage held conferences (especially in the United States) on his work, he prepared his answers in advance for the customary, mandatory Q&A sessions that followed, without having any idea of what he would be asked. Just as the group work experience puts the artist’s statute in doubt, the meta-question “What’s that got to do with it?” puts into doubt the complex, compulsorily consequential question-answer.

A big hug,

Cesare

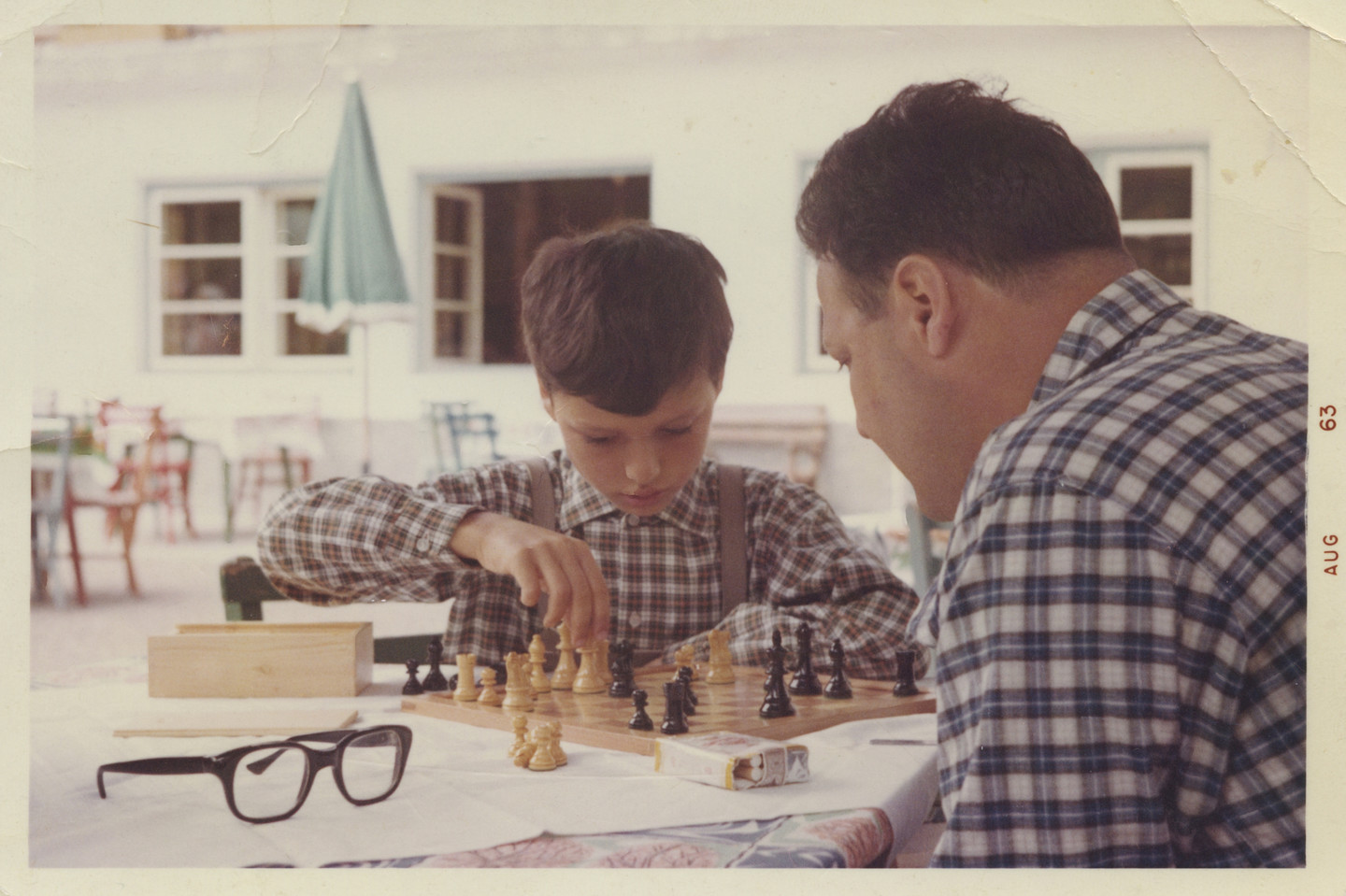

Cesare Pietroiusti, Chess game with dad, Cortina d’Ampezzo (?), August 1963, color photograph