Gió Marconi

Fredrik Værslev. World Paintings

THEY ARE THE WORLD, PART I

Dieter Roelstraete

Sebbene il germe dei World Paintings abbia attecchito per la prima volta nella mente di Fredrik Værslev dalla metà degli anni 2000 – l’occasione nacque allora dall’incontro fortuito con le bandiere dipinte in stile hard edge dall’artista svedese Olle Baertling che all’esterno del Moderna Museet di Stoccolma fluttuavano al vento – e sebbene Værslev abbia iniziato i suoi “flag paintings” più di due anni fa, è difficile pensare a una serie di opere in grado di cogliere, alla loro maniera semi-astratta e minimalista, le insolite scosse cosmiche di questo 2020, annus horribilis tra i peggiori, in modo più struggente e incisivo, soprattutto per l’impatto che questi radicali mutamenti hanno sortito sul business arciglobale e squisitamente cosmopolita dell’arte contemporanea.

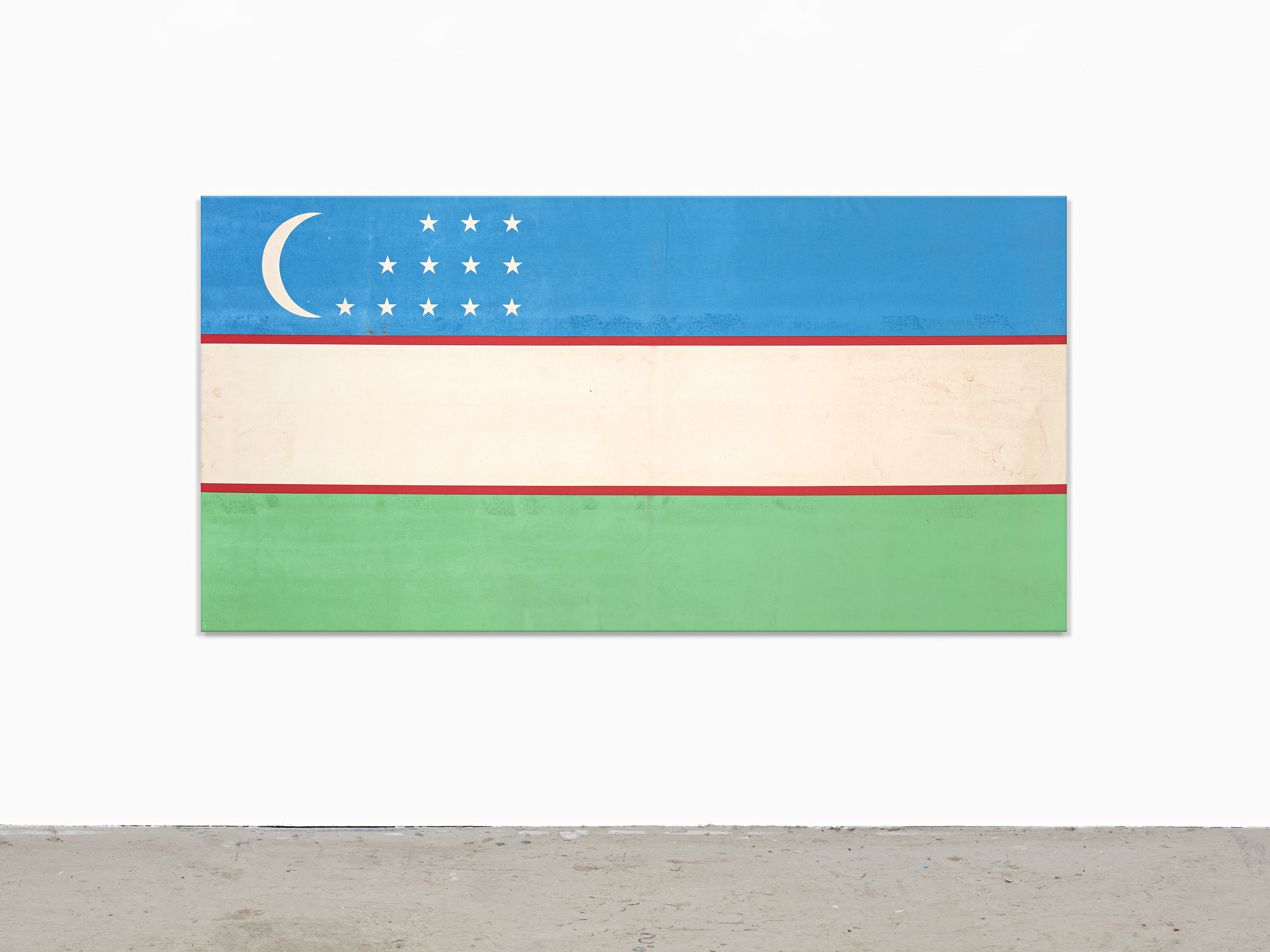

I dodici dipinti oggetto della mostra “raffigurano” vari paesi del mondo di tutti e cinque i continenti: Bielorussia (dipinto eseguito, inutile a dirsi, molto prima che le agitazioni post-elettorali spazzassero via l’ultima dittatura pseudo-stalinista in Europa), Repubblica Turca di Cipro Nord (non un vero stato, in quanto non riconosciuto a livello internazionale), Inghilterra, Israele, Republica di Corea, Nauru, Pakistan, Panama, Seychelles, Trinidad e Tobago, e infine Uzbekistan. (Se questa selezione vi sembra casuale e spiazzante – ebbene, lo è. A parte il fatto, per nulla insignificante, che tutte queste bandiere, considerate sia da un punto di vista pittorico, sia da una prospettiva politica, contengono in sé il colore bianco: il bianco, tanto per cominciare, delle tele non trattate di Værslev.) Il significato delle opere d’arte è alquanto mutevole, naturalmente, ma val la pena riflettere sulla differenza che in appena sei mesi può esserci nella concezione, produzione e ricezione di queste stesse opere – contributo sobrio e diretto di Fredrik Værslev alla lunga storia della “flag art”, sacra e controversa al tempo stesso. Nel momento in cui scrivo (fine agosto 2020), non è ancora chiaro se l’artista potrà a recarsi a Milano dalla nativa Norvegia per l’allestimento e l’inaugurazione della sua esposizione – il tutto a causa del protrarsi degli effetti della pandemia COVID-19, il più dirompente e distruttivo degli eventi capitati all’economia mondiale dai tempi della grande depressione di novant’anni fa.

Lo scoppio di questa pandemia ha imposto il divieto a livello internazionale di compiere viaggi all’estero, il che ha sortito un impatto spropositato sul mondo dell’arte contemporanea e su settori collaterali come quello dell’industria culturale e dell’intrattenimento, sulla rete globale dell’istruzione superiore e della ricerca et similia. (In altre parole, il nostro mondo – quello dei servizi apparentemente non essenziali. Quest’estate ho scritto un saggio di 10.000 parole sui World Paintings di Værslev senza poterli vedere dal vivo, effettuando delle studio visits tristemente destinate, a causa del coronavirus, alla sfera virtuale e incosistente della videochiamata.) In effetti, per quanto l’arte in sé, con la sua impenetrabilità senza luogo e senza tempo alla catastrofe cellulare, possa indubbiamente superare la tempesta di questa emergenza sanitaria globale senza nemmeno un graffio – ars longa, vita brevis, giusto? – lo stesso non può necessariamente dirsi riguardo al complesso ecosistema del mondo dell’arte contemporanea – una “bolla” se mai ce n’è stata una – che, nella sua storica e complessa condizione di prodotto della globalizzazione, è inestricabilmente legata ai viaggi aerei e al costante e naturale attraversamento delle frontiere da parte di persone e cose, habitués del mondo dell’arte e opere.

L’arte contemporanea è quel fenomeno squisitamente globale per cui i confini di un paese e le antiquate nozioni di identità nazionale non dovrebbero aver importanza, se non come argomenti ormai storicizzati esclusivamente destinati a promuovere ricerche d’archivio. Ma eccoci al punto, i confini territoriali e le identità nazionali si sono rafforzate nel continente europeo, in modo mai visto prima dall’attuazione del Trattato di Schengen nella metà degli anni Novanta, inaugurando così una nuova era di immobilismo e radicamento assolutamente aliena a quanti di noi – per coloro che leggeranno questo comunicato stampa intendo tutti noi – erano abituati per anni, se non per decenni, a volare comodamente attraverso quegli antiquati confini di appartenenza territoriale.

Da questo punto di vista, i World Paintings di Værslev assumono il tono elegiaco di un addio (si spera temporaneo) all’utopica illusione di un villaggio globale dell’arte e ci riportano a quando il mondo era l’ostrica di ciascuno, alle gallerie semideserte di oggi, malinconico memoriale di una globalità gettata in un completo e apparentemente irreversibile caos. In alternativa, tuttavia, se vista dall’opposta prospettiva della Realpolitik del rafforzamento delle frontiere – poiché una delle grandi illuminazioni della pandemia è stata dmostrare quanto fosse facile far risorgere il concetto di nazionalità – i World Paintings potrebbero anche essere letti come riflessione sul persistere del sentimento patriottico, sul rinnovato interesse verso principi di identità nazionale nell’era Brexit-Modi-Putin-Trump, che in gran parte viene espresso così appassionatamente dall’attaccamento della gente, davvero singolare, alla bandiera, uno dei simboli più enigmatici e potenti. Questo, è chiaro, pone nettamente in risalto i World Paintings come gesto politico – a inevitabile detrimento (è questa la termodinamica dell’arte) del suo contenuto estetico, o dei suoi esiti formali. Questo è, in sintesi, il problema di tutta la “flag art”, di cui Værslev deve essere stato da sempre consapevole – per quanto, forse impreparato al radicale mutamento delle condizioni in cui la sua idea di flag art avrebbe compiuto la prima apparizione pubblica. Il “problema” in questione ci pone la domanda se il dipinto di una bandiera possa realmente essere considerato tale: potremo mai vedere il dipinto e non “solo” la bandiera? In un certo senso, Værslev – ben cosciente del peso della nazionalità nella lingua franca internazionale dell’arte, e certamente interessato ai molti enigmi sollevati dal rigurgito di fervore nazionalista a livello globale – ha tentato di eludere la domanda ponendosi l’inquietante quesito opposto: potrà mai una bandiera essere “solo” un dipinto? Certo che sì – un dipinto minimalista in stile hard-edge, un segnale di chiarezza e risolutezza laddove non ne esiste alcuna. Eccetto, forse, che nell’arte.

Il presente testo è stato concepito in forma di post scriptum a un saggio monografico scritto dall’autore durante l’estate 2020, ed esclusivamente dedicato ai World Paintings di Fredrik Værslev.

Fredrik Værslev. World Paintings

THEY ARE THE WORLD, PART I

Dieter Roelstraete

Although the seeds for World Paintings were first planted in Fredrik Værslev’s mind back in the mid-2000s – the occasion, back then, was a chance encounter with the hard edge flag paintings of the Swedish artist Olle Baertling, billowing in the breeze outside the Moderna Museet in Stockholm – and although Værslev first started working on his “flag paintings” more than two years ago, it is hard to think of a suite of works that, in their quasi-abstract minimalist manner, more painfully and poignantly capture the singular cosmic tremors of 2020, this most horribilis of anni, especially in terms of the impact these seismic shifts have had upon the arch-global, quintessentially cosmopolitan business of contemporary art. Assembled here are twelve paintings “depicting” various countries of the world, from all five continents: Belarus (a painting executed, needless to add, long before post-electoral unrest swept the last pseudo-Stalinist dictatorship in Europe), the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (not an actual, i.e. internationally recognized state), England, Israel, Republic of Korea, Nauru, Pakistan, Panama, Seychelles, Trinidad and Tobago, and Uzbekistan. (If this seems like a disorientingly random selection – well, it is. Except for the not-so-meaningless fact, seen from both a painterly and political perspective, that all of these flags have white in them: the white, to begin with, of Værslev’s untreated canvas.) Artworks’ meanings change all the time, of course, but it is worth reflecting on the difference a mere six months makes in the conception, production and reception of these very works – Fredrik Værslev’s straight-faced, understated contribution to the long history, both hallowed and contentious, of “flag art”. At the time of writing (late August 2020), it is still not clear whether the artist will be able to travel from his native Norway to Milan for the installation and opening of his exhibition – all because of the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the single most disruptive, disastrous event to befall the world economy since the Depression ninety years ago. With this particular coronavirus outbreak has come a worldwide ban on international travel, which has disproportionately impacted the contemporary art world alongside adjoining sectors of the culture and entertainment industries, the global network of higher education and research, and the like. (Our world, in other words – that of the seemingly not-so-essential services. I wrote a 10.000-word essay about Værslev’s World Paintings this past summer without ever laying eyes on the real thing – a painful, corona-enforced first, with studio visits doomed to the weightless virtuality of the FaceTime-sphere.) Indeed, although art itself, in its placeless, timeless imperviousness to cellular catastrophe, will doubtlessly weather the storm of this global health emergency without so much as a scratch – ars longa, vita brevis, right? – the same may not necessarily be said about the complex ecosystem of the contemporary art world – a “bubble” if ever there was one – which, in its historical predicament as a product of globalization, is so inextricably bound up with air travel and the constant, effortless crossing of borders by both people and things, art world denizens and artworks. Contemporary art is that quintessentially global phenomenon for which national borders and antiquated notions of nationhood or national belonging aren’t supposed to matter, except perhaps as fully historicized subject matter deserving only of patronizing archival scrutiny. But here we are, national borders and national identities fully reinforced across the European mainland, in ways not seen since the implementation of the Schengen Agreement in the mid-nineties, ushering in a new era of immobility and rootedness utterly alien to those of us – and as far as the generic addressee of this press release is concerned, that means all of us – used to years, indeed decades of frictionless flight across those old-fashioned markers of territorial belonging. Seen from this vantage point, Værslev’s World Paintings take on the elegiac tone of a (hopefully temporary) farewell to the utopian specter of art’s global village, back when the world was everyone’s oyster, the sparsely peopled gallery now a wistful memorial to a globality thrown in utter, seemingly irreversible disarray. Alternately, however, when seen from the opposing perspective of the Realpolitik of reinforced borders – for one of the great insights of the pandemic has been how easy it has proven to be to raise the notion of nationhood from the dead – World Paintings could also be read as a rumination on the persistence of national feeling, of the renewed relevance of notions of national belonging in the Brexit-Modi-Putin-Trump era, much of it so passionately expressed in people’s truly curious attachment to that most enigmatic and potent of all symbols, the flag. This, of course, shines a stark spotlight on World Paintings as a political gesture – at the expense, inevitably (such are the thermodynamics of art), of its aesthetic content, or its formal achievement. That, in a nutshell, is the problem of all “flag art”, of which Værslev must at all times have been aware – though he may perhaps not have been prepared for the radically altered conditions under which his take on flag art would have to make its first public appearance. The “problem” in question asks of us whether a painting of a flag can ever be truly a painting: can we ever see the painting, and not “just” the flag? To a certain extent, Værslev – who is keenly aware of the weight of nationhood on the international lingua franca of art, and who is definitely interested in the many conundrums raised by the return of nationalist fervor around the globe – has sought to circumvent this question by asking its unnerving inverse: can a flag ever be “just” a painting? Of course it can – of the hard-edge, minimalist variety, signaling clarity and decisiveness where none can really ever exist. Except, that is, in art.

This text was conceived as a post scriptum to a monographic essay written by the author over the course of the summer of 2020, dedicated solely to Fredrik Værslev’s World Paintings.