Matteo Zauli

Matteo Zauli is a cultural manager and curates shows, events, residences and festivals related specifically to the use of ceramics in contemporary languages in Italy and abroad. He teaches cultural management and lectures in the Course for Curators at the Bologna Academy of Fine Arts. He lives in Faenza and is the director of the Carlo Zauli Museum, which he founded in 2002. Works from the Museum were exhibited in “Solo figura e Sfondo”, the first exhibit in the Courtesy Emilia-Romagna series curated by Davide Ferri at Arte Fiera 2019.

Alfonso Leoni, beyond the dialectic of ceramics

As I see it, what makes a work of art really interesting is the energy that’s released by a dialectic relationship and that at times intensifies based on differences. Since I want to talk about the Emilia-Romagna region - in which Arte Fiera is a real diamond set right in the middle – it won’t surprise you that I’ll tell you about a dialectic relationship involving my city. Faenza is both a province with about sixty thousand inhabitants and a city overflowing with ancient and contemporary art, where in ancient times painted vases were made and now a hundred visual artists, ceramicists, designers, and artisans make a living (often happily) from their work.

Among the ceramicists, the ones who do sculpture undertake the extremely arduous task of being appreciated in the visual arts tout-court, going beyond the boundary marked by galleries, museums, and collectors.

It’s a problem of identity and frustration that commenced after Leoncillo and Fontana had brought matter to a full sculptural and conceptual dimension, and that has plagued dozens of ceramicists here for 50 years. For example, my father considered himself a sculptor starting in 1960, only after creating a series of monumental works for architecture and public clients, and after having stopped making everyday objects.

But he never received full recognition as such in Italy.

Likewise (but for other reasons), the same was true for another sculptor from Faenza who probably represents, along with Nanni Valentini, the highest conceptual peak in international ceramics in the last 30 years of the 20th century: Alfonso Leoni.

In a city considered the white island and the factory of priests in left-wing Romagna for the entire 20th century, Leoni was the most progressive figure in a territory which, in its one square kilometre, contained artists whose parents were partisans (like my father) or quasi-political refugees, like Panos Tsolakos, who emigrated from the military dictatorship in Greece. In this square kilometre, the International Museum of Ceramics and the Institute of Art provided historical assumptions, training, work, and testing ground for much-needed contemporary expression.

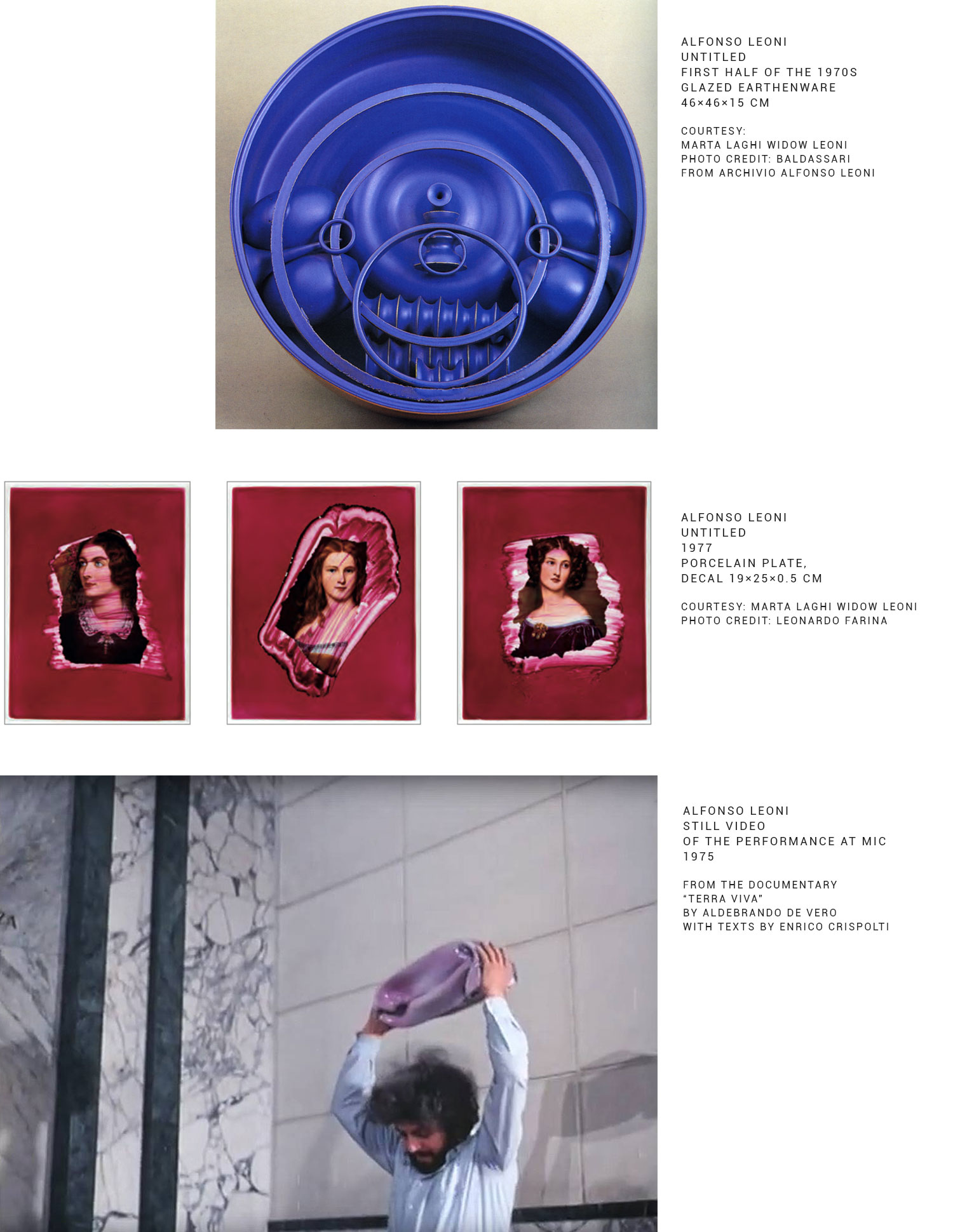

It was at the International Museum, in 1975, that Leoni achieved one of the peaks of this golden age of ceramics: for a documentary on contemporary Italian ceramics shot for RAI, the Italian television network, by Enrico Crispolti and Aldebrando De Vero, he gathered a group of students and began flinging to the ground and destroying some of his historical and most recent ceramics, technically perfect, gleaming in their wonderful vitreous enamel and full of deep historical, anthropological, and philosophical references. Then, before bewildered observers, he rearranged the fragments with raw clay, remodelling it as a large, coarse sphere without any of the technical refinement that his works had always had.

As if to say that technical excellence in art is more a limit than a value, even if all artists use it to the best of their ability. This observation is especially obvious and sacrosanct in ceramics.

Five years later, just when he was receiving international recognition for his work, Leoni died at the age of 39. There remain many ceramics that still surprise us, an archive, books, and stories by people who knew him.

Ceramics is now very fashionable, and countless artists come to Faenza to work this material: as my father said, it’s like a virus, and if you catch it, you’re never the same.

It’s a history more than a material, as old as Man but always as bright as the crystal coating the enamel, giving it eternal freshness.

Just like Leoni’s works, which still seem fresh from the furnace.